This book stands out as the highlight of the year so far.

First, even if you are not very interested in the topic the book form is amazing. Chris is a very good writer.

The book unfolds through numerous chapters, each reading like a compelling short story. Despite being integral to the plot, these chapters are well-structured, ensuring a seamless connection with preceding content, and allowing for easy navigation of the topic.

The author easily simplifies complex concepts and looks into them from different perspectives. I was fucking hooked up reading this ;)

Now, onto the subject matter – a true masterpiece.

Damn, I honestly don't even know where to start.

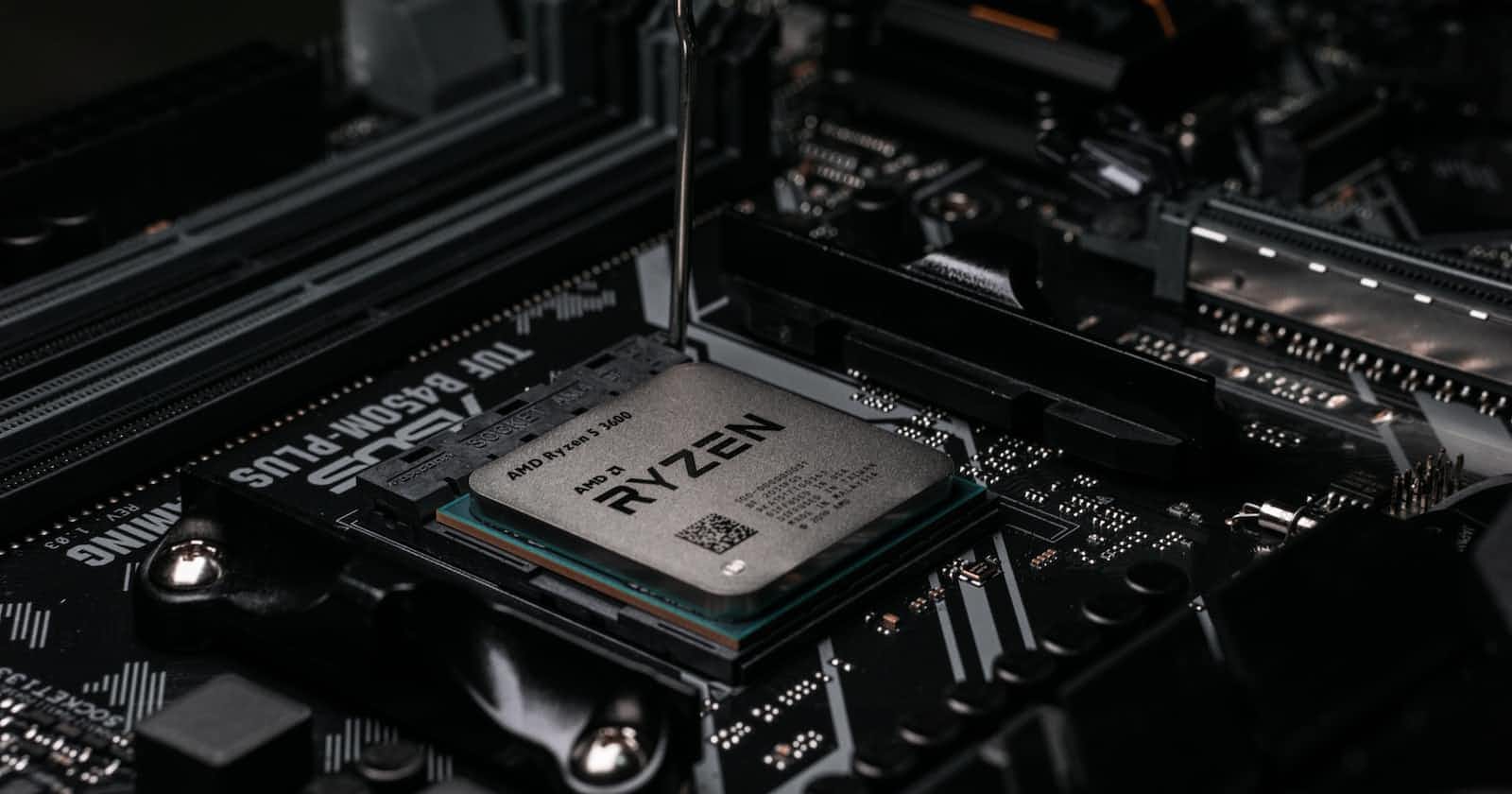

So yeah the book is about chips or microprocessors or how the hell you want to call it. But it's just a part of the book. It's more like a snapshot of the last decade.

The role of computing power in shaping the course of future conflicts is emphasized. While WWII was influenced by steel and metal, and the Cold War by atomic weapons, the upcoming major wars are likely to be determined by computing power. The chip industry has produced more transistors than the combined output of all goods throughout human history, highlighting its unparalleled significance. In the era of AI, the scarcity isn't data but processing power, with a finite number of semiconductors available for storing and processing data.

The book delves into the military implications, emphasizing the importance of technological superiority. Electronics, particularly semiconductors, are crucial for maintaining a leadership role in this domain. However, a challenge arises as the U.S. defense may soon rely on foreign sources for cutting-edge semiconductor technology.

The difficulty in producing powerful microchips is highlighted, impacting military supply chains and reshaping the nature of warfare. USSR wouldn't be able to last long during the Cold War without its advanced spy factories. They were (are) so damn good at it that you probably already know without me putting some facts here.

In 1963, the same year the USSR established Zelenograd, the city of scientists working on microelectronics, the KGB established a new division, Directorate T, which stood for teknologi. They had an understanding that relying on oil and stealing was in the past and new gold was advanced microchips. Fortunately for us, spying is not enough. Chris explains it simply by two main obstacles:

1. Simply stealing a chip didn’t explain how it was made, just as stealing a cake can’t explain how it was baked. The recipe for chips was already extraordinarily complicated. And because of Moor's law, even if you would be able to produce a super powerful chip after working on it for a few years, in the end, it would be outdated as people from whom you steal will move so far ahead. Soviet spies were among the best in the business, but the semiconductor production process required more details and knowledge than even the most capable agent could steal.

2. You need a market. You can't just spend all your efforts on expensive technology without any RIO and customer feedback. It's like trying to design the greatest thing beforehand without any iteration, and people from tech know how bad this idea is.

Luckily red army failed to produce something good and changed its strategy to focus on other areas of potential military dominance. Life doesn't work like that. We all know how it was and the Persian Gulf War was the final crisis for the Red regime: quality was overtaking quantity. In the U.S they were saying that it's a triumph of silicon over steel and War Hero Status Possible for the Computer Chip.

The Cold War was over; Silicon Valley had won.

The narrative transitions to modern times, touching on significant topics such as nazirusso invasion of Ukraine, ASML and TSCM, lithography, Intel and Apple CPUs, NVIDIA GPUs, and their impact on AI and military technology. China emerges as a formidable challenger, aiming to surpass the U.S. in both missiles and bytes.

Current and future wars are about tech. But tech as an industry whatsoever. This race isn't about a single technology but about complex systems. It's not only about R&D but also effective management processes. The staggering complexity of producing computing power shows that Silicon Valley isn’t simply a story of science or engineering. Technology only advances when it finds a market. The history of the semiconductor is also a story of sales, marketing, supply chain management, and cost reduction.

To conclude, I want to say that it is very naive to believe that you understand the world. This thing is so damn hard and it is worth exploring its corners, as something small as a chip can affect your life and the survival of nations. It's not only about this book topic, it's in general. Let's try to stop thinking only in patterns and look a bit outside of the box. There could be a huge stream (of data, value, informatics, whatever) that you don't know about but that will change the direction of your ship.

p.s. Let's hope that Taiwan is simply the source of the advanced chips that both countries’ militaries are betting on. And not most likely future battleground.

But hope is not a strategy.